Overview

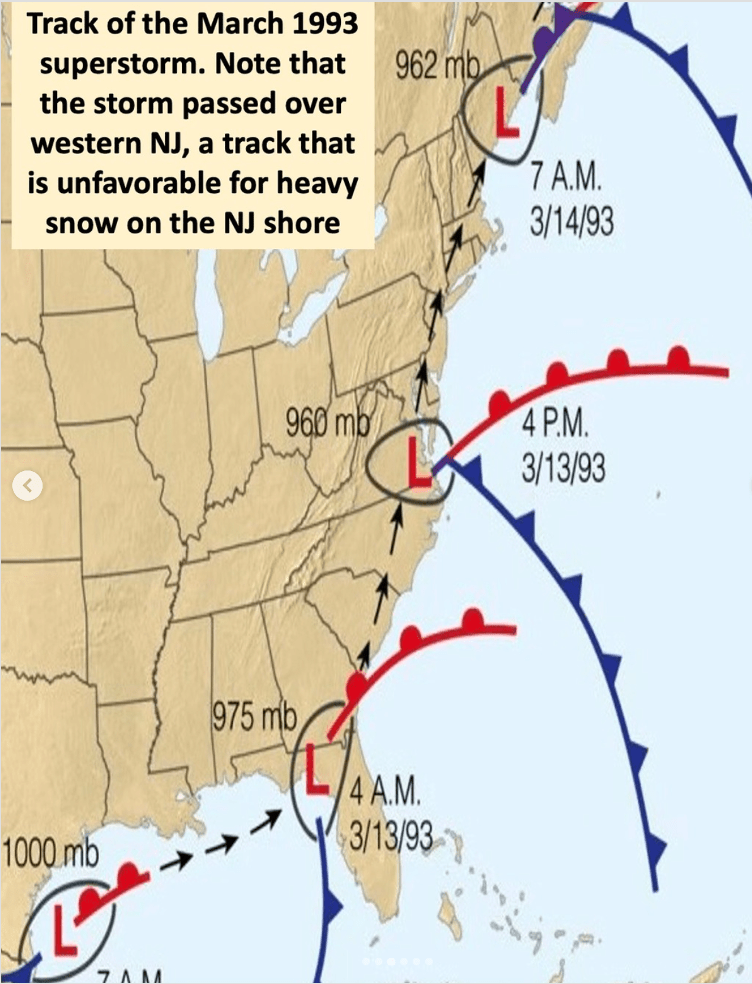

During the period March 11-13 1993, inclusive, a storm tracking from the eastern Gulf Coast into New England produced a swath of devastation that had rarely been seen in these areas. From destructive storm surges across FL and tornadoes across the Southeast to records snowfall across portion of the southern and eastern US, the storm earned the nickname “Storm of the Century”. While its impacts were not quite as dramatic along the Jersey Shore as other places in the eastern US, the storm was a reminder that winter was not down with NJ quite yet.

Before the Storm

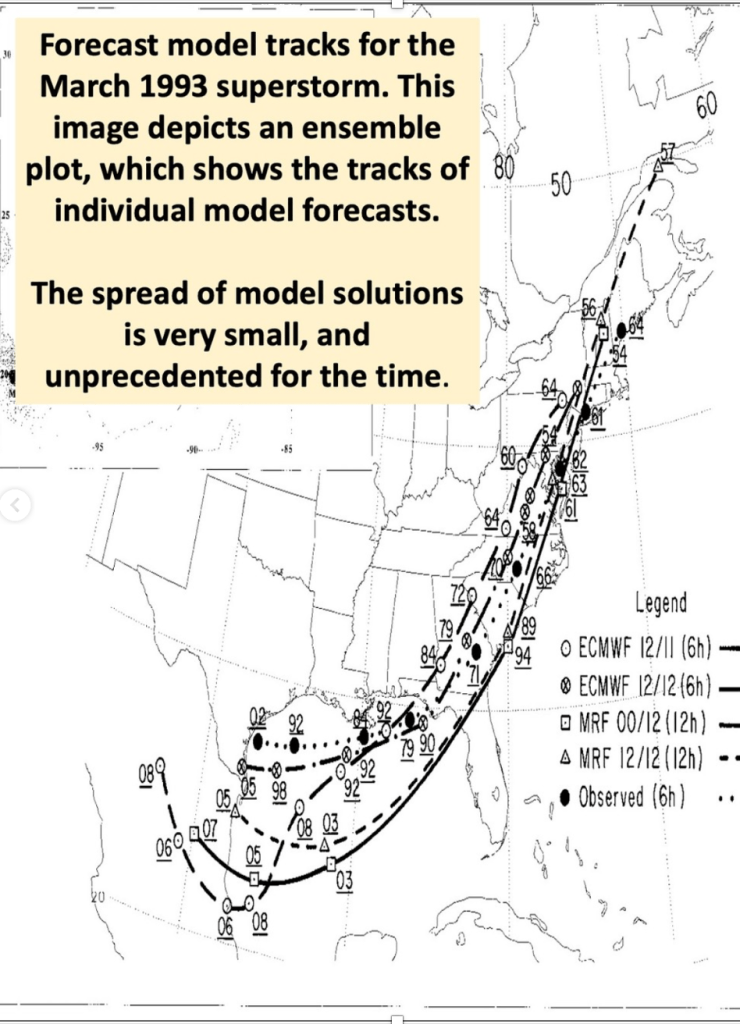

Five days before the storm reached peak intensity near the East Coast, there was a remarkably strong signal in the model data that a significant storm would affect the region. Working for the National Weather Service in Atlantic City, NJ at the time, I was unaccustomed to models agreeing on much with respect to storms until the event was much closer in time and space. Plotting the most recent US and European solutions together on the same map underlined just how strongly the signal was for a powerful storm at the time. Still in a period when models were not as reliable as they are now, it was often difficult to know when to trust them during potentially impactful weather events. For this storm, the signal was clear, allowing forecasters to provide nearly unprecedented lead time and confidence it what would be a catastrophic event for portions of the Eastern US.

Even with the increased confidence, National Weather Service forecasters chose to analyze more information before raising alarms for the NJ Shore. The first watches were issued with the 4 AM forecast on Friday, March 12th, and the first warnings (including Blizzard Warnings for inland areas) were issued about 12 hours later. Remarkable model consistency led forecasters to employ seldom-used verbiage about life-threatening conditions in their statements ahead of the system.

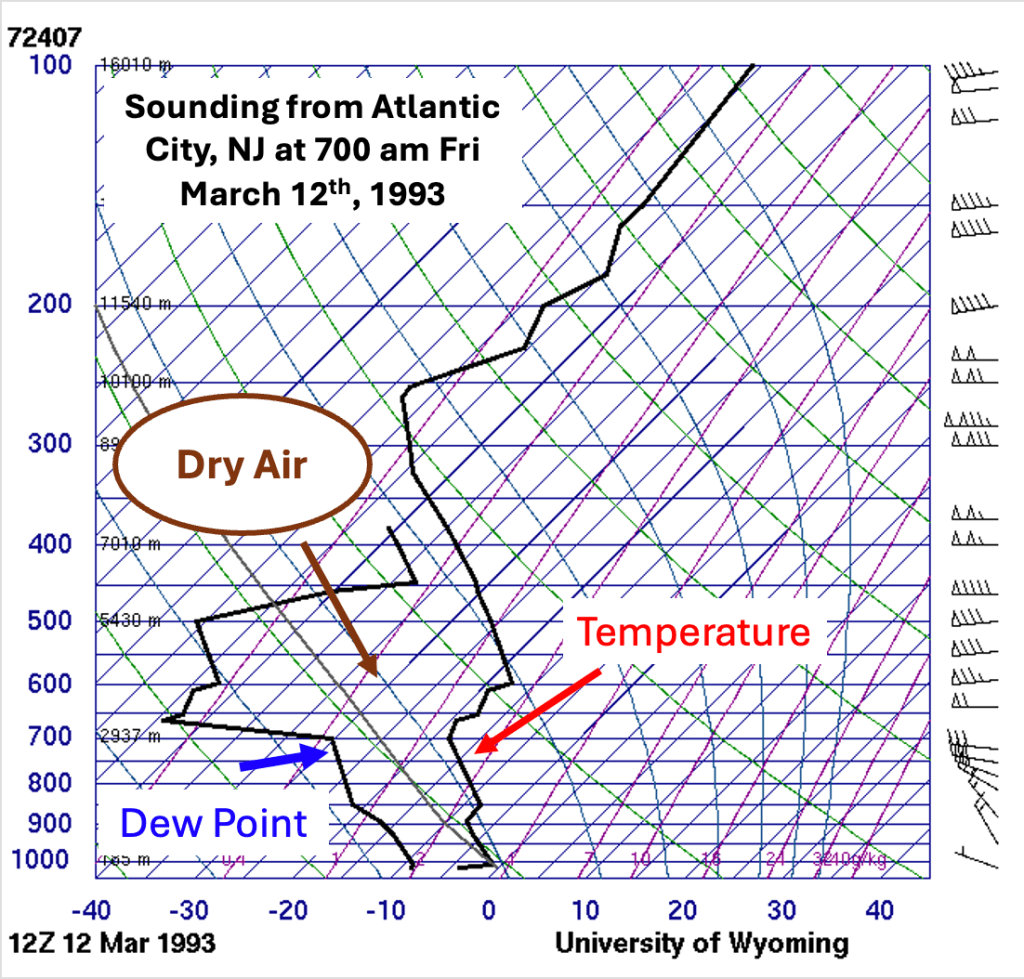

Before the storm along the Jersey Shore, weather conditions were seasonable for the middle of March, with highs in the 40s and lows in the 20s. The airmass in place was quite dry, which is often a portend to precipitation remaining in the form of snow longer than would otherwise be expected. The reason for that is beyond the scope of this blog entry, but a more in-depth explanation as to why dry conditions ahead of storm might mean more snow can be found here.

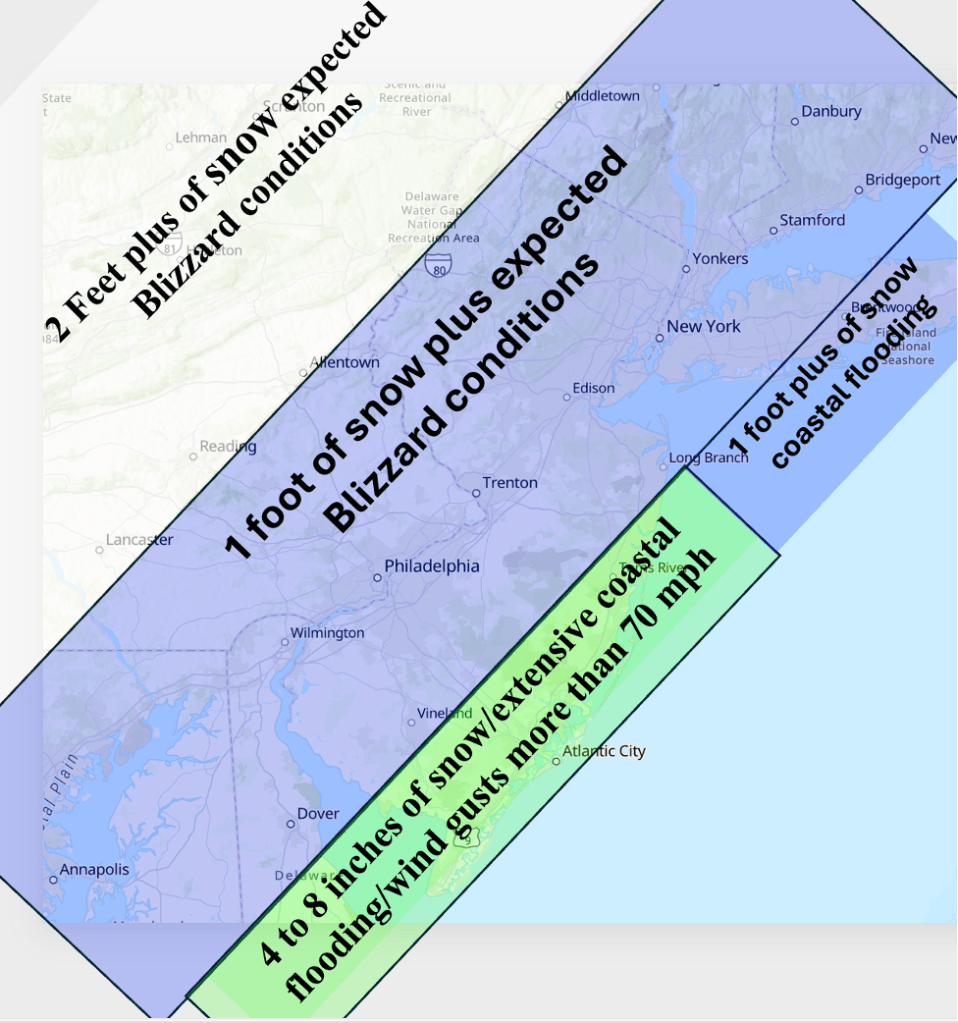

As is the case for most winter storms, the biggest forecast problem was the precipitation type and snowfall amounts along the NJ shore. Often when storms affect the region, winds shifting to the northeast or east allow milder temperatures to creep inland, changing snow to rain along the coast. Forecasters were concerned about that for this forecast as well, and initially indicated that the coast of central and southern NJ would see snow change to rain as warmer air came in from the ocean.

Elsewhere, with cold air locked in place by high pressure across northern New England, there was little doubt that the precipitation would fall in the form of snow. Given model output for precipitation amounts for much of interior NJ and southeast PA, snowfall forecasts of a foot plus were common. Strong winds were expected to gust to near hurricane force near the coast, resulting in considerable blowing and drifting of snow during the heart of the storm Saturday evening into Sunday morning.

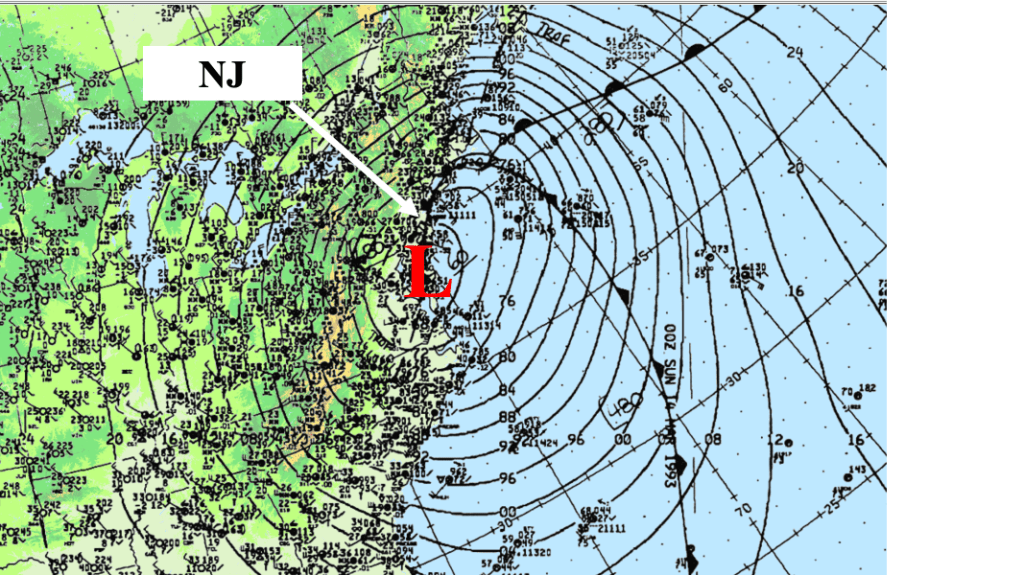

The Superstorm of 1993

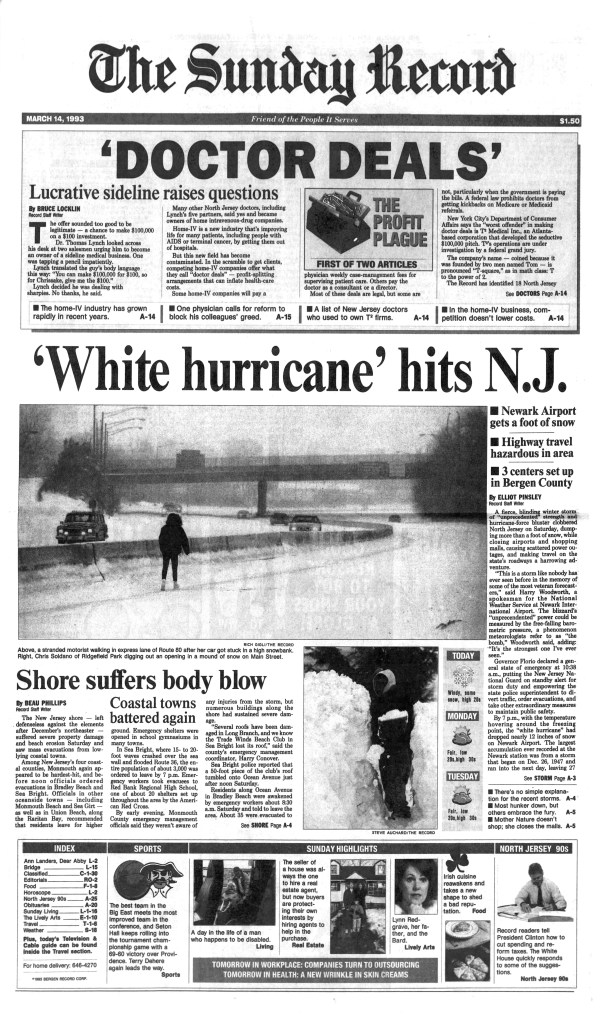

Snow overspread the Jersey Shore during the morning hours of Saturday, March 13, 1993. Even with an easterly wind pushing milder ocean air inland, the precipitation remained mainly snow, a testament to the dry air in place when the snow started. However, the warmer ocean temperatures eventually changed the snow to rain from south to north. By late afternoon, heavy rain was falling from Seaside Heights south along the coast, buffeted by 70 MPH winds, as well as considerable coastal flooding.

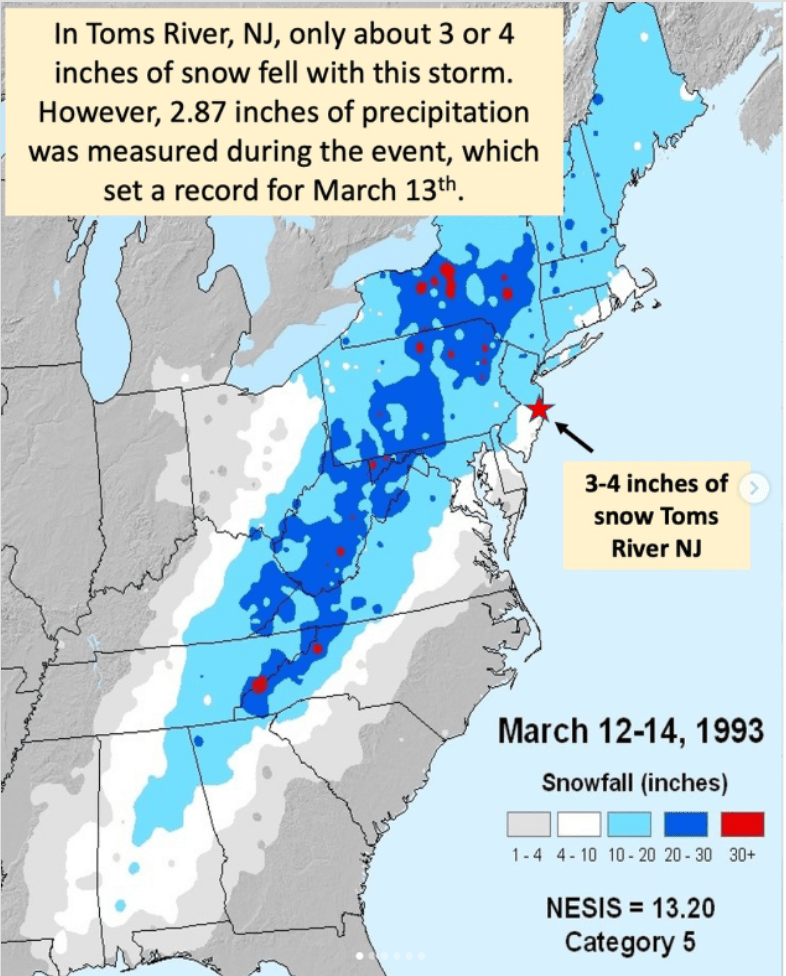

Working as a National Weather Service meteorologist at the office in Atlantic City, NJ (ACY), I was scheduled to work the evening shift (and beyond). Before my shift, I was in Toms River, where I knew the snow would last longer than further south. Driving south on the Garden State Parkway, I saw just rain on my trip to ACY. My brother measured about 3.5 inches of snow before the snow changed to rain, and a total of 2.87 inches of liquid equivalent was measured for March 13th, a new daily rainfall record.

Further inland, a blizzard raged across the remainder of central and northern NJ, as well as eastern PA and nearby NY state. By 700 PM Saturday 13th, 1993, heavy snow extended from southern ME south into NJ and PA and VA., where snow was falling at the rate of 2-3 inches an hour, something that does not happen often in this area. Winds shifted back to the northwest with the passage of the storm, but by that time the precipitation intensity decreased, leaving mainly light snow along the NJ Shore late Saturday night.

At the NWS office in Atlantic City, we received mainly rain during the event. Daily record rainfall amounts were logged for ACY (the location of the NWS office, which is about 10 miles west of Atlantic City itself) and the downtown location. In addition, ACY also received 2.9 inches of snowfall, a record snowfall for the date. Elsewhere along the Jersey Shore, snowfall amounts ranged from 2 to 3 inches across southeast NJ to more than a foot near Sandy Hook. Significant coastal flooding (including the back bay areas of Barnegat Bay) and power outages plagued the coast through the weekend.

Further inland, between 12 and 24 inches of snow was measured at the end of the storm, and strong winds caused considerable blowing and drifting of the freshly fallen snow. Though life had come to a temporary standstill over much of the region, the early warnings convinced people to shelter in place, and as bad as the storm battered the area, the Jersey Shore weathered it as well as could be expected.

Aftermath

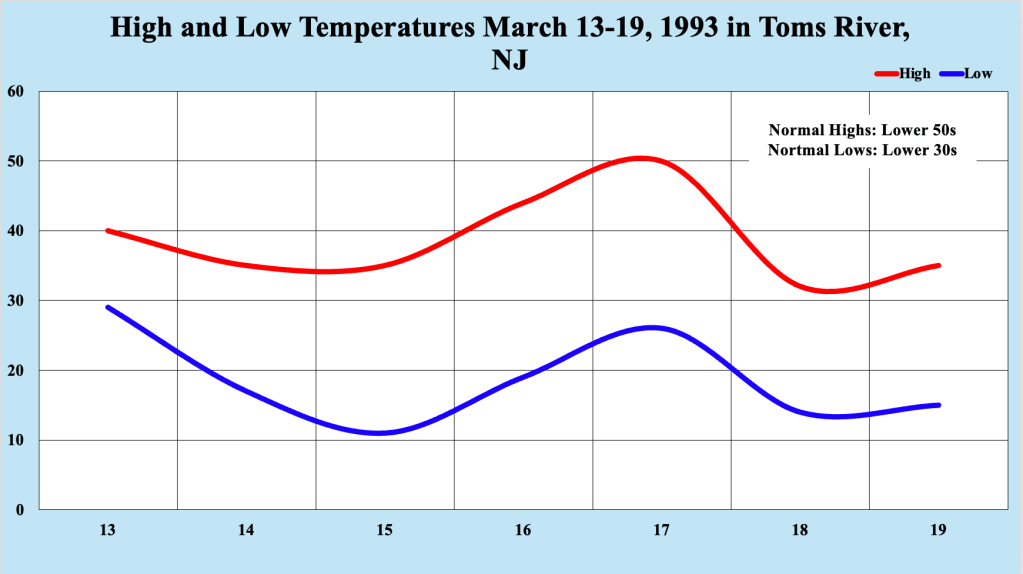

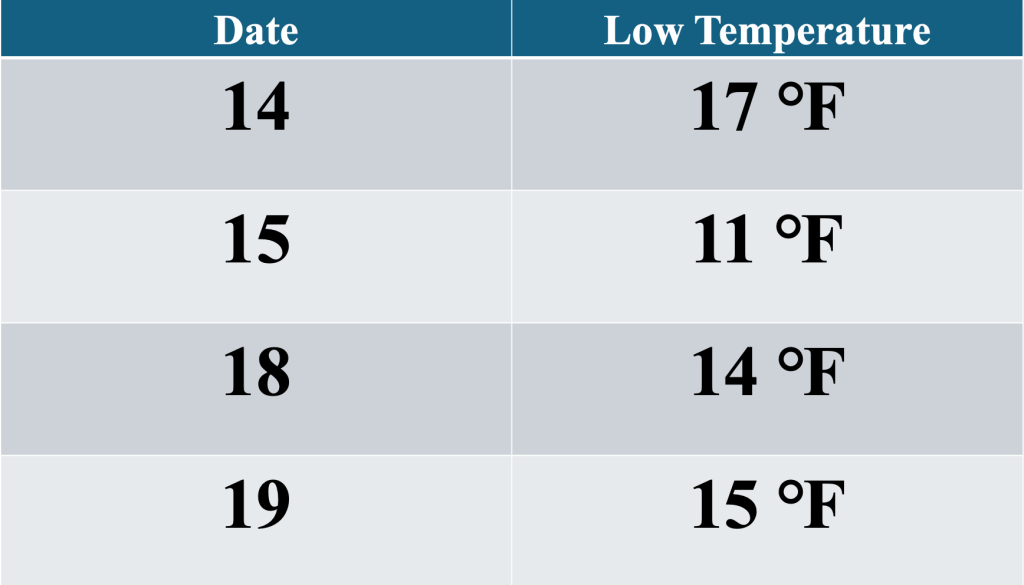

Behind the storm, arctic air covered the mid Atlantic and Northeast states. The cold air ensured that snow, ice and rainwater left behind from the storm froze in place, resulting in treacherous travel on secondary roads along the Jersey Shore through much of the week following the storm. Temperatures averaged 15 to 25 degrees below normal for the Bellcrest section of Toms River, NJ, and four daily record low temperatures established during the cold snap. On March 18th, 1993, the high temperature struggled to reach the freezing mark, and the 32 degree high temperature that day is still the latest a high of 32 degrees or lower was measured at this station.

Another unexpected consequence of the storm was the water quality for both the Atlantic Ocean and Barnegat Bay along the Jersey Shore. My brother remarked “after this event, the water in the Barnegat Bay and the ocean along the Jersey Shore looked much cleaner than I ever remembered it looking. Environmental improvements since the low point of the 1970s kept it that way after the storm.” The force of the battering ways and high tides cleaned the water in these bodies of water, leaving them cleaner than they had been in recent memory.

Leave a comment