Overview

Before the advent of satellite images and automated surface observations, weather observers would identify the types of clouds in the sky, as well as their height as part of routine weather observations. Identifying the types of clouds can provide information on what is occurring in the atmosphere in that location. In the 1930s, the National weather Service (known then as the Weather Bureau) developed charts describing the state of the sky, which aided forecasts in determining the state of the atmosphere at standard times throughout the day and night.

During my days as a weather forecaster, my first rule of forecasting was simple: look out the window. Knowing what is occurring now can give an observer (or a forecaster) a good idea what might happen in the short term (during the next few hours). For example, if I saw altocumulus castellanus in the sky driving into work in the morning during the summer I knew we would have a busy afternoon and evening with thunderstorms. This cloud chart was developed from the NWS chart, augmented by my experience with the different cloud types, punctuated by pictures of each type taken by myself for my brother.

There are three clouds categories outlined in the chart: Low clouds, Middle clouds, and High clouds. Clouds at each level of the atmosphere can yield clues as to what is occurring now, and what might happen in the future.

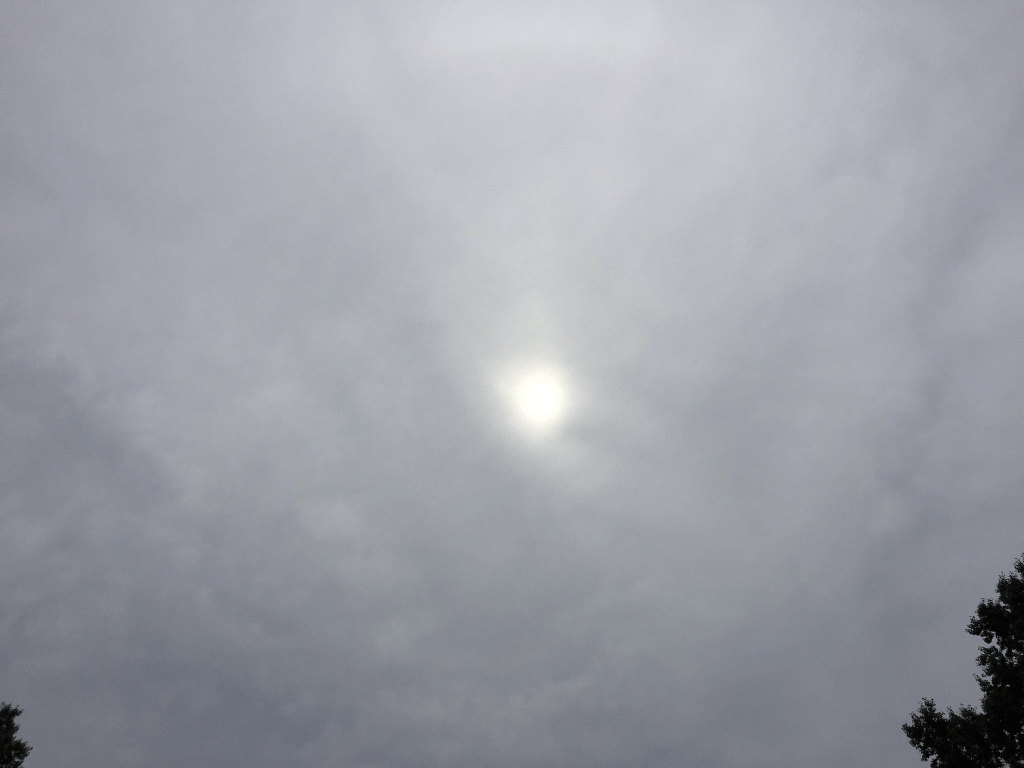

M1 – Translucent altostratus

Altostratus clouds are composed of mostly opaque water droplets or a mix of water droplets and ice crystals, found between 7,000 feet and 20,000 feet, and occasionally thin enough to allow the sun or moon to shine through. Because of their altitude, altostratus rarely produce precipitation, and the depth of the clouds are insufficient to support processes for precipitation to form.

Often altostratus is a transition between thickening cirrus clouds and lower nimbostratus clouds, as the moisture in the airmass increases. Increasing and thickening altostratus is a good indicator of approaching steady precipitation (generally within 12 to 24 hours). This image shows altostratus that is thin enough to allow sunshine through the veil, but does not produce a halo.

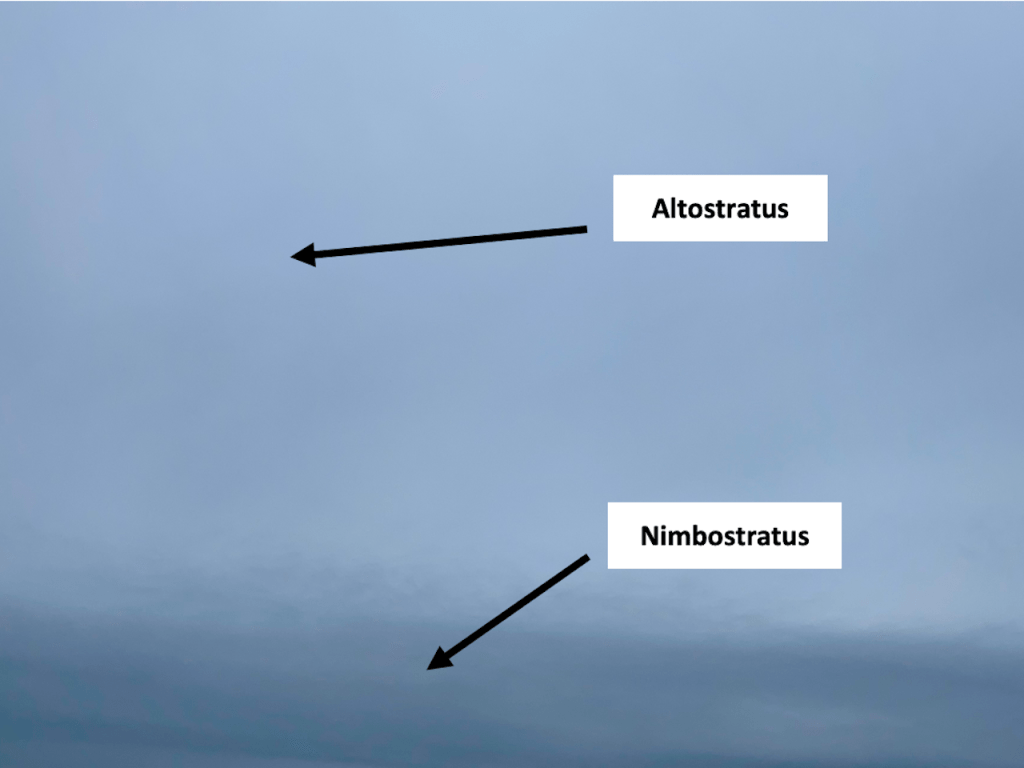

M2 – Thic opaque altostratus

Altostratus clouds are composed of mostly opaque water droplets or a mix of water droplets and ice crystals, found between 7,000 feet and 20,000 feet, and occasionally thin enough to allow the sun or moon to shine through. Because of their altitude, altostratus rarely produce precipitation, and the depth of the clouds are insufficient to support processes for precipitation to form.

Often altostratus is a transition between thickening cirrus clouds and lower nimbostratus clouds, as the moisture in the airmass increases. Increasing and thickening altostratus is a good indicator of approaching steady precipitation (generally within 12 to 24 hours). As the airmass moistens, altostratus and nimbostratus can and do coexist, with precipitation falling as nimbostratus becomes more prevalent.

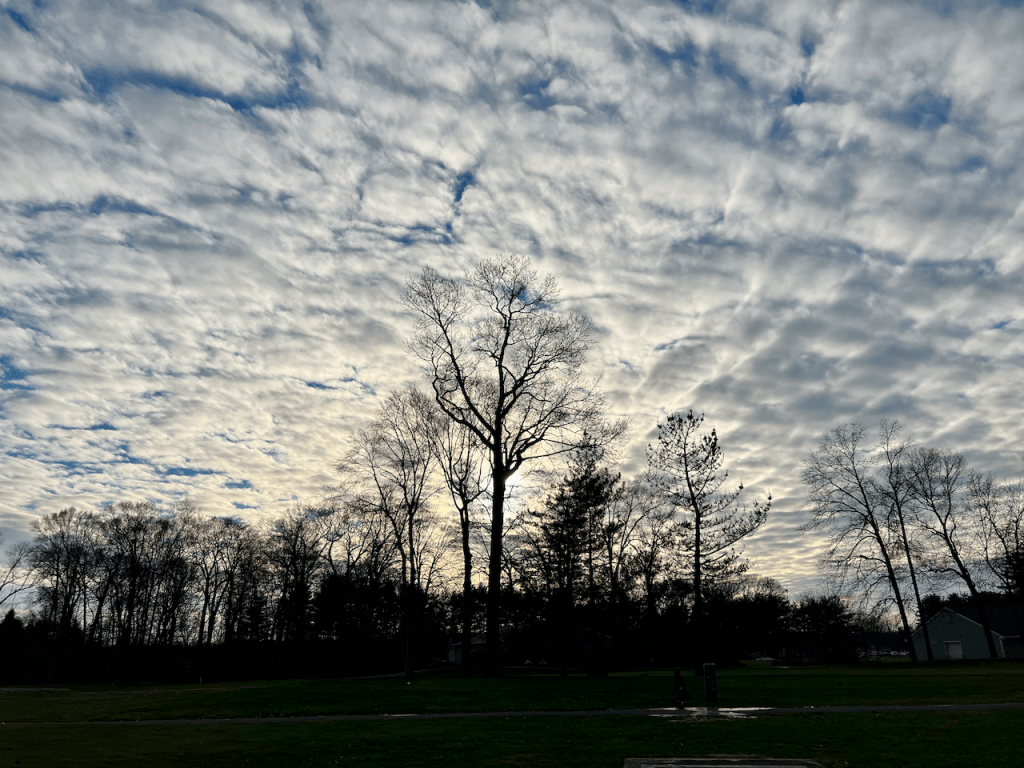

M3 – Translucent altocumulus in a continuous sheet

Altocumulus clouds form higher in the atmosphere than cumulus clouds, typically between 7,000 and 15,000 feet. Usually flatter and thinner than their lower counterpoints, these clouds form in the presence of moisture and lift in the mid-levels of the atmosphere, without instability in place. Because of this, they rarely produce precipitation, but can be predecessors of showers and storms if the clouds lower.

Altocumulus often appear as patches or sheets, and occasionally seem to have scales (some varieties of altocumulus have been said to produce a “mackerel sky”). Occasionally altocumulus is thin enough to allow the sun or moon to be visible. In this image, the altocumulus is in a continuous sheet, with breaks that allow the setting sun to be visible on a late December afternoon in Plainsboro, NJ.

(Photo credit: Jeff Hayes)

M4 – Altocumulus standing lenticular

Altocumulus Standing Lenticular (ACSL) clouds form in the presence of fast moving air forced up and over mountains or hills that are perpendicular to the direction of the wind flow above the topographic obstruction. ACSL develop in between mountains where moisture is present. ACSL clouds can form anywhere downstream of mountains and hills, but are more common across the western United States, due to its complex terrain. ACSL also indicate the presence of severe turbuluence, an aviation hazard. These clouds are continuously developing and dissipating in more or less the same place, so ACSL clouds appear to be standing still. Because of their peculiar look and the fact that they appear to be stationary, ACSL clouds are often mistaken as UFOs.

M5 – Multiple levels of altocumulus

Altocumulus clouds are typically indicative of instability in the mid-levels of the atmosphere, which is why they bear some resemblance to stratocumulus in the lower levels. Much like stratocumulus, altocumulus clouds usually have little vertical extent, as the air above them is warmer and drier, forcing the moisture to spread out. Banding of altocumulus clouds often suggests channels of warm air riding up and over the cooler air in place, and the banding shows where the upward motion associated with the warmer air is the strongest.

In this image (which was captured in Nishinomiya, Japan), there are at least two levels of altocumulus, indicating that rising air is occurring at these levels. Ahead of approaching precipitation, it is not unusual to see one or more decks of altocumulus that lower with time, eventually becoming stratocumulus. Dry air below the altocumulus generally prevents precipitation with these clouds, but they can be an indication that precipitation is possible in the future.

M6 – Altocumulus formed by the spreading of cumulus

This type of altocumulus is like stratocumulus (L4), except these clouds form as a result of moist, unstable air rising ahead of a cold front or mid-level disturbance. The moisture and instability allow pre-existing clouds (such as cumulus or cumulonimbus) to produce showers and thunderstorms. When these cells weaken, they lose their connection to the lower-level moisture that fed the storms but continue to rise in the unstable airmass.

Often these clouds will spread out, and begin to resemble stratocumulus, just at a higher level. When the altocumulus forms, the areal coverage of showers and thunderstorms diminishes. This image was taken in Skyline View, PA, just as a mid-level disturbance crossed the location. To the east, storms continued, but to the west, clouds started to thin out.

M7 – Altocumulus with altostratus

Altocumulus clouds typically indicate instability in the mid-levels of the atmosphere, which is why they resemble stratocumulus in the lower levels. Much like stratocumulus, altocumulus clouds usually have little vertical extent, as the air above them is warmer and drier, forcing the moisture to spread out. Banding of altocumulus clouds often suggests channels of warm air riding up and over the cooler air in place, and the banding shows where the upward motion associated with the warmer air is the strongest.

In this image (which was captured over Brainerd Lake in Cranbury, NJ), there are at least two levels of altocumulus, indicating that rising air is occurring at these levels. Most of the clouds are opaque, but there are some breaks, which means that the dry air from above is helping to erode the altocumulus. Though the air below the clouds is dry, there are some hints at virga particularly in the clouds in the background.

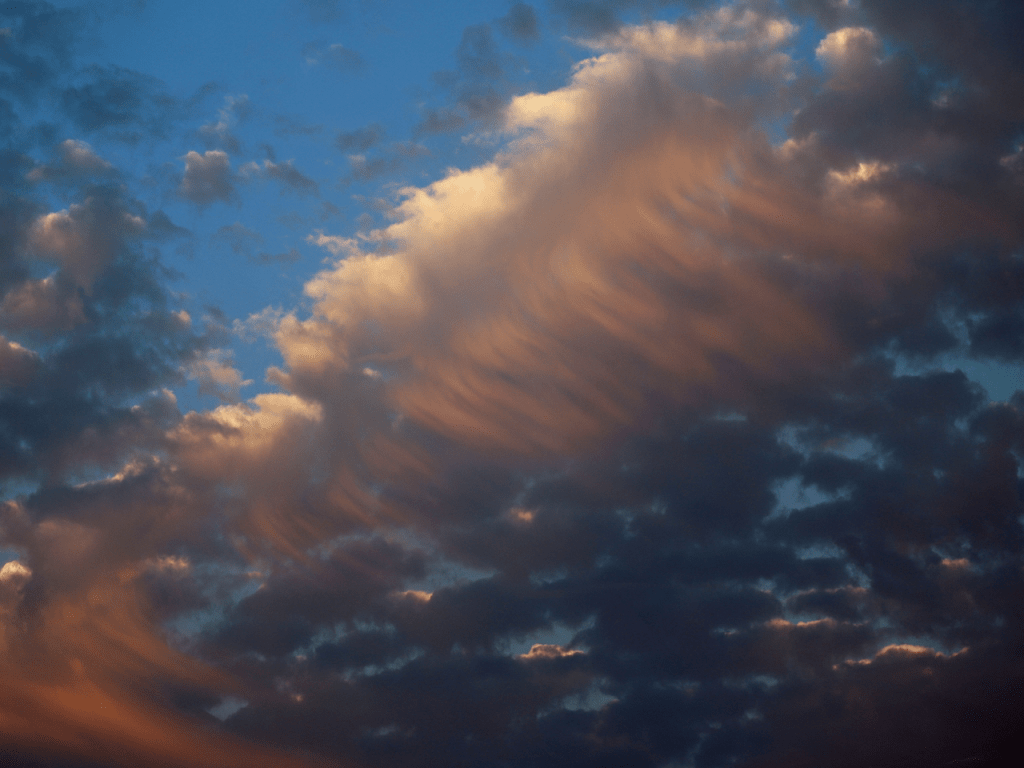

M8 – Altocumulus castellanus

Known as altocumulus castellanus clouds (often abbreviated as ACCAS by weather forecasters), this type of cloud generally forms between 6,500 and 10,000 feet over the eastern US, often showing vertical development reminiscent of cumulus clouds during the warm season. They indicate the presence of instability in the mid-levels of the atmosphere. When they appear during the cool season (early March in this example) or in the late afternoon, ACCAS provide interesting cloud formations, but almost never rain (outside of a few sprinkles). The atmosphere is simply too dry to support storm development.

However, during the warm season (April through September), ACCAS developing in the morning hours is usually indicative of numerous and often strong thunderstorms during the afternoon and evening hours. As the lower atmosphere warms after a relatively cool start to the morning, it allows access to the mid-level instability in which these clouds usually form. The presence of ACCAS can presage the development of strong thunderstorms in the afternoon hours, often with strong winds, hail, and heavy rainfall.

The ACCAS clouds in this image developed over Hershey PA during the late afternoon in March 2023.

M9 – Altocumulus causing a chaotic sky

Altocumulus clouds generally indicates the presence of instability above the surface, though most altocumulus do not display any significant vertical development. Altocumulus at more than one level points to rising air causing by lift at different altitudes. Altocumulus at various levels can result in a chaotic looking sky, particularly if the sunshine illuminates some of the layers and not others.

For the most part (especially over the eastern United States), the height of cloud bases associated with the altocumulus clouds preclude much precipitation. However, if there is enough lift in the levels containing the altocumulus, virga can occur, adding to the chaotic nature of the sky. In this image (taken in Plainsboro, NJ in July 2021), it is easy to see the various levels of altocumulus, with the lower levels appearing darker, and the higher levels illuminated by the setting sun. Perhaps the most striking aspect of the image is the way the virga (in the center of the screen) is highlighted, adding to the chaotic nature of the sky.

(Photo credit: Jeff Hayes, great shot Jeff!)

Leave a comment