Overview

Before the advent of satellite images and automated surface observations, weather observers would identify the types of clouds in the sky, as well as their height as part of routine weather observations. Identifying the types of clouds can provide information on what is occurring in the atmosphere in that location. In the 1930s, the National weather Service (known then as the Weather Bureau) developed charts describing the state of the sky, which aided forecasts in determining the state of the atmosphere at standard times throughout the day and night.

During my days as a weather forecaster, my first rule of forecasting was simple: look out the window. Knowing what is occurring now can give an observer (or a forecaster) a good idea what might happen in the short term (during the next few hours). For example, if I saw altocumulus castellanus in the sky driving into work in the morning during the summer I knew we would have a busy afternoon and evening with thunderstorms. This cloud chart was developed from the NWS chart, augmented by my experience with the different cloud types, punctuated by pictures of each type taken by myself for my brother.

There are three clouds categories outlined in the chart: Low clouds, Middle clouds, and High clouds. Clouds at each level of the atmosphere can yield clues as to what is occurring now, and what might happen in the future.

L1 – Daytime cumulus

This type of cumulus usually forms in the late morning hours, as the sun warms the lowers levels of the atmosphere, resulting in air bubbles that rise. Once the air bubbles become saturated, they form clouds that appear billowy. As the air bubbles encounter colder temperatures, the cumulus stops building, and eventually dissipates. During this process, edges of the clouds may expand and contract, causing the shapes of the clouds to change. By evening, with the heating of the day having passed, all of the clouds disappear.

Typically, daytime cumulus do not produce precipitation, as the airmass in which they form is too dry for rain or snow showers, though a sprinkle or flurry is possible during the afternoon. This image was taken by a drone over Fairville Park in West Hanover, PA.

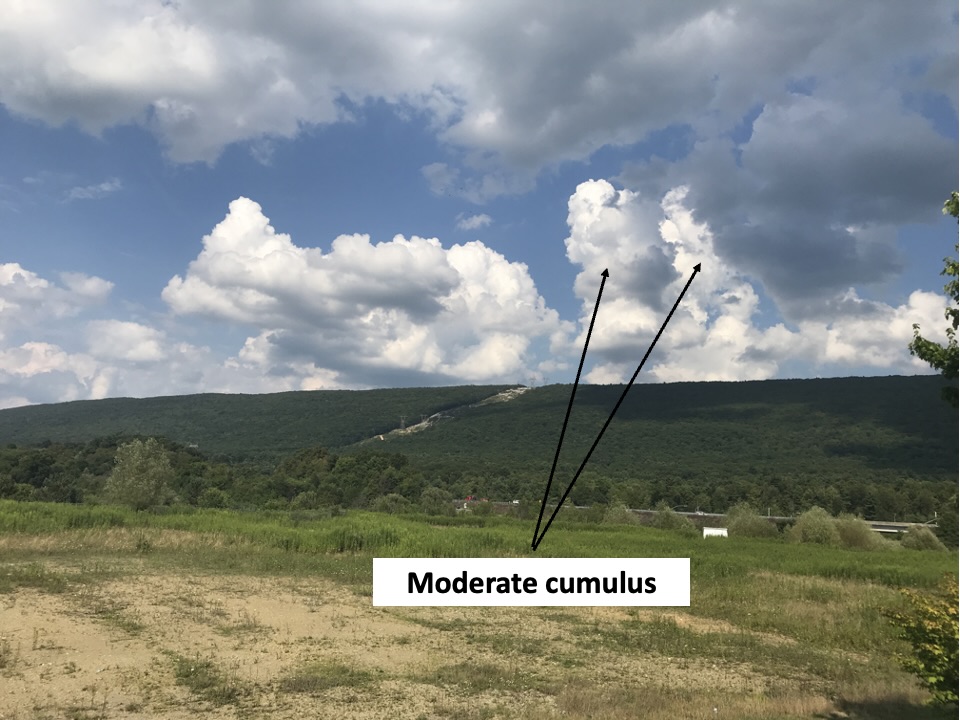

L2 – Moderate cumulus

Moderate cumulus forms in much the same way as daytime cumulus, but the airmass is generally warmer and contains more moisture. The combination of warmth and moisture allows the cumulus to build more quickly, as the air parcels are generally much warmer than their surroundings. The ribbon of rising air associated with the parcels is known as an updraft. While daytime cumulus has no updrafts, the updraft in the moderate cumulus is strong enough to allow a column to form, which is usually tall enough to distinguish it from the main cumulus clouds.

On their own, moderate cumulus tend to produce only light showers. However, in a favorable environment, moderate cumulus can grow into cumulonimbus, which could support heavy rainfall. This image was captured near Altoona, PA. These cumulus clouds grew into cumulonimbus and produced thunderstorms about two hours later.

L3 – Cumulonimbus

Cumulonimbus clouds are towering in vertical extent, usually forming in an airmass the supports rapidly rising air parcels found in warm and humid conditions. The rising parcels form a strong updraft, which allows the cloud tops rise well above the parent cumulus cloud. Often there are one or more updrafts in a quickly developing cumulonimbus cloud, resulting in several towering clouds tops. In this image, you can see several updrafts, each featuring bright white tops. These tops are glaciated, or are composed of almost all ice crystals, indicative of a strong thunderstorm in the developing stage.

This cumulonimbus is not quite mature, since it does not feature an anvil top, a flat cloud that sits atop the storm. However, even in the developing stage, the cumulonimbus cloud can produce heavy rain, strong winds and hail. This storm was photographed at East Hanover Community Park in Grantville, PA.

L4 – Stratocumulus formed by spreading cumulus

Once cumulus development reaches its peak in the early afternoon, they become “flattened” by drier and warmer just above them. Known as a subsidence inversion, air moving downward from above stops the development of the cumulus, forcing the clouds to become spread out. As the clouds spread out, they cover more of the sky, often resulting in mostly cloudy conditions. Most often cumulus spreading into stratocumulus occurs during the cool season (roughly October through April), as the darker bottoms of the stratocumulus often contrast with the breaks in the blue skies seen between the clouds.

Typically, the stratocumulus dissipates before nightfall, as heating from the sun in the main force driving cloud development. Sprinkles or flurries can occur as the cloud formation changes shape, but generally there is simply not enough moisture in the air to support anything more than spotty, light precipitation. This image was snapped by a drone looking south over the Susquehanna River near Riverfront Park in Wrightsville PA.

L5 – Stratocumulus not from cumulus

Stratocumulus (like the continuous area seen in the image above) often forms when moisture is trapped beneath what is known as a subsidence inversion. Warmer and drier air just above the cloud layer acts like a ceiling, forcing the moisture to spread out along and under the ceiling. Typically, skies are mainly clear above the cloud layer, but few breaks in the clouds are noted, as is the case in this image. If the warmer and drier air remains in place above the cloud layer, the stratocumulus deck can stay in place for days.

Since the moisture feeding the clouds is relatively shallow, little or no precipitation is expected. The persistent stratocumulus deck in this image was captured over Boulder CO, which was remarkably lush and green at the time.

(Photo credit: Jeff Hayes)

L6 – Stratus

Stratus clouds develop in the presence of abundant low-level moisture, generally associated with a low-level flow ranging from north to southeast. The moisture spreads out along a low-level inversion (where warmer and drier air lies just above the low-level moisture, preventing the moisture from dissipating). Conditions favoring the development of stratus clouds are generally stable, meaning that stratus will remain in place, sometimes days at a time, until a change in the weather pattern forces it to exit. With little or no lift and shallow moisture, precipitation is unlikely when stratus is in place. This image was recorded on an overcast day in Skyline View, PA.

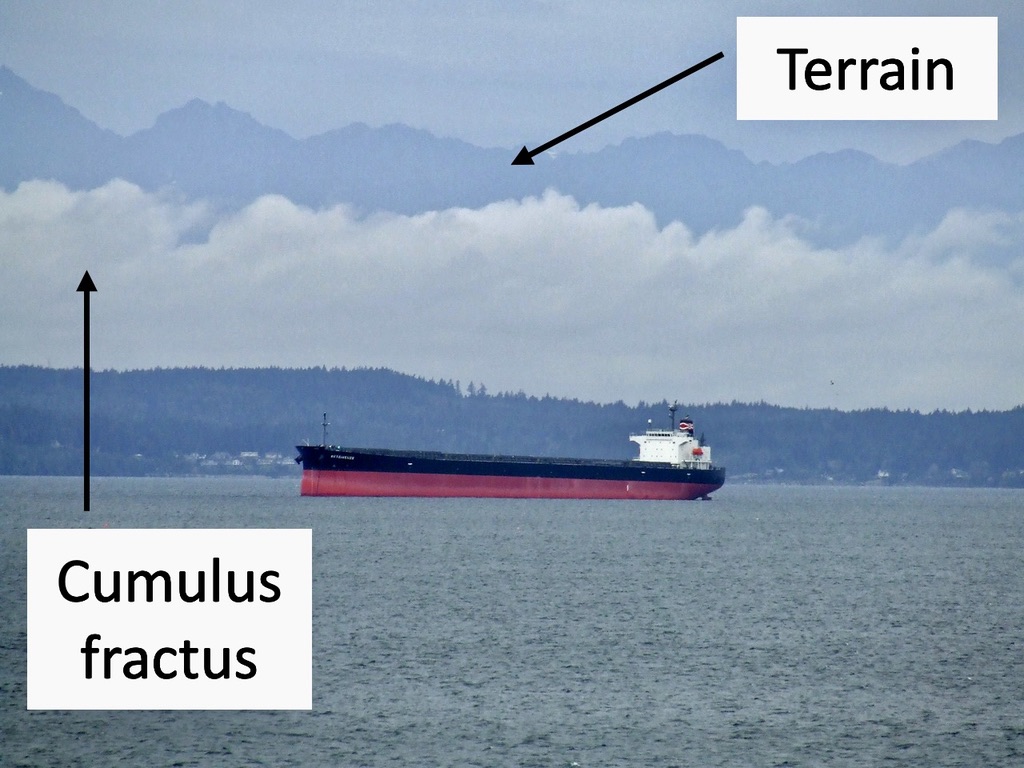

L7 – Stratus fractus or cumulus fractus

Both stratus fractus and cumulus fractus form in the presence of precipitation, as the falling rain or snow increases the low-level moisture to the point of saturation. Stratus fractus forms when there is little in the way of lift or instability in the airmass, and the precipitation associated with these clouds is generally light (possibly falling as drizzle). While stratus fractus can form anywhere with favorable conditions, they can often be found near hills and mountains, where the upslope flow along the terrain helps saturate the low level airmass.

Cumulus fractus forms in very much the same way as stratus fractus, but low-level lift may allow these clouds to have limited vertical development. Like stratus fractus, cumulus fractus is typically associated with light precipitation, and more readily forms in the presence of terrain. Both cloud types can pose an aviation hazard, as the low clouds and precipitation can produce low ceilings and poor visibility. This image shows cumulus fractus on the western shore of Puget Sound, just west of Seattle, WA, with terrain in the background.

(Photo credit: Jeff Hayes)

L8 – Stratocumulus and cumulus at different levels

Typically, stratocumulus clouds and cumulus clouds develop due to different physical processes. Stratocumulus forms when drier and warmer air just above the clouds force them to spread out and prevent much in the way of vertical extent. Cumulus clouds usually form in the presence of unstable conditions, which allows air parcels to rise if they are warmer than the surrounding air, resulting in vertical cloud development. With such disparate conditions in which these clouds form, they are not often seen in tandem.

However, there is at least one set of conditions that allow stratocumulus and cumulus to exist coincidentally. During the warm season, it is not unusual for stratocumulus to be in place during the morning hours, until sufficient sunshine allows the drier and warmer air just above the clouds to sink, causing the stratocumulus to start dissipating. If there is any instability above the stratocumulus layer as it breaks up, that instability could allow cumulus clouds to form in the breaks.

In this image, the morning stratocumulus clouds are breaking as warmer and drier air just above it is causing the clouds to slowly break up on the east side of the Thames River in London UK. Almost immediately, cumulus clouds start to pop in the breaks in the stratocumulus clouds, and the tops of the cumulus clouds are white (indicating the presence of ice), as opposed to the slate gray of the stratocumulus.

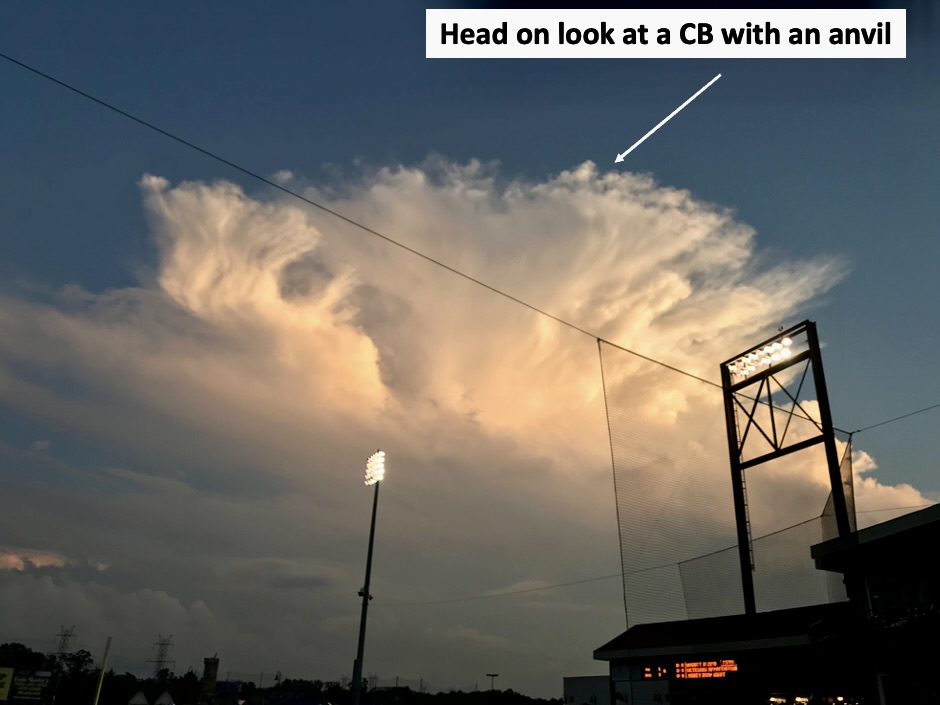

L9 – Cumulonimbus with an anvil

Cumulonimbus clouds (CB) are very large, tall cumulus clouds, and indicate the mature stage of a thunderstorm. As the storm peaks in intensity, it forms an anvil, which is the top of the storm being blown in the direction of the mid-level wind. By this stage, the CB are producing strong winds, heavy rain, hail and possibly tornadoes. Over the eastern United States, CB clouds with anvils are seen much less often than in the central Plains, mainly because of tree cover and terrain. In addition, heavy rainfall often obscures the details of the CB, which also makes these clouds difficult to discern.

In this image (captured in Waldorf, MD), a mature CB has just developed an anvil, with fibrous clouds pointing toward the observer. The top of the CB is illuminated by sunlight reflecting sunshine to the west, and by continuous in-cloud lightning. Because the track of the storm took it away from the observer, the camera caught an excellent look at the anvil.

Leave a comment